Irish Legal Heritage: The Ballot Act of 1872

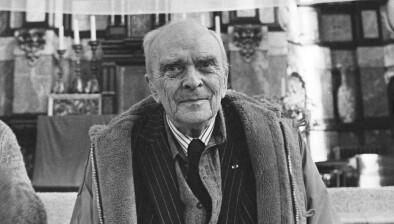

Statue of Charles

Stewart Parnell

in Dublin

The secret ballot was introduced in Britain and Ireland in July 1972 by the Ballot Act of 1872, with the aim of mitigating the effects of bribery, intimidation, and coercion in elections.

Section 2 of the Act outlined the new procedure for voting, which provided for voters to “secretly” mark their vote, and to fold it up “to conceal his vote” before placing it in a closed ballot box. While the ballot was “not absolutely secret” due to the fact that voter numbers allowed “an elector’s name and vote” to be correlated “in the event of a petition” (Crook and Crook, 2007), this electoral reform was revolutionary – not least in Ireland.

The issue of coercion in Ireland was discussed during the second reading of the bill, where Liberal MP Edward Leatham said that the deplorable “mob intimidation in Ireland” constituted “deliberate and organised interference with freedom of election”. Leatham’s description of the situation is worth setting out in full:

“Tenant-farmers are collected by the estate agent, in some instances many days before the election, placed upon strings of cars, handed over to the military, escorted as prisoners, or believing themselves to be prisoners, by horse, foot, and artillery, and all the imposing paraphernalia of an army in occupation of an enemy’s country, to the polling-place, kept therein forced custody and with locked doors until the day of poll, not even permitted to avail themselves of the ministrations of religion, and then finally polled in the presence of the landlord or the agent.”

One important beneficiary of the secret ballot in Ireland is said to have been Charles Stewart Parnell, who was first elected as a member of the House of Commons in in 1875. While there is disagreement as to the extent to which the Act assisted Parnell’s success, the introduction of the secret ballot meant that “it was not so easy to drive electors like swine to the market” (O’Neill Daunt, cited in Hurst, 1965), and the Irish voter was no longer “powerless against the intimidation of his social superiors”.

Seosamh Gráinséir