UK: Supreme Court: Refusal to compensate men whose convictions were overturned does not breach presumption of innocence

The requirement for a person to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that they did not commit an offence in order to access compensation for a miscarriage of justice does not breach their right to presumption of innocence, the Supreme Court has ruled.

About this case:

- Citation:[2019] UKSC 2

- Judgment:

- Court:UK Supreme Court

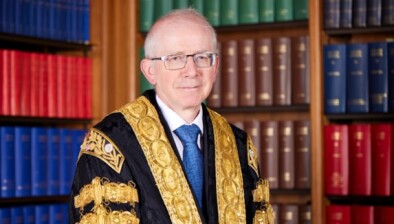

- Judge:Lord Mance

The question in the appeals was whether the definition of a “miscarriage of justice” in section 133 of the Criminal Justice Act 1998 (as amended by section 175 of the Anti-social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act 2014), which has the effect of restricting awards of compensation to cases in which a new or newly-discovered fact shows beyond reasonable doubt that the person did not commit the offence, is incompatible with the presumption of innocence in article 6(2) of the European Convention on Human Rights.

By a majority of 5-2, the Supreme Court dismissed the appeals this morning. Lord Mance delivered the leading judgment, Lady Hale, Lord Wilson, Lord Hughes and Lord Lloyd Jones delivered concurring judgments, and Lord Reed and Lord Kerr dissented.

The appeals were brought by Sam Hallam and Victor Nealon, who respectively spent around seven years and 17 years in prison before their convictions were quashed in light of newly-discovered evidence, and were subsequently refused compensation under section 133 of the 1998 Act.

Reasons for the judgment

In the previous case of R (Adams) v Secretary of State for Justice [2011] UKSC 18, the Supreme Court identified four categories of case, of progressively wider scope, as a framework for discussing the meaning of “miscarriage of justice” for which an applicant could be compensated in accordance with section 133:

- where the fresh evidence shows clearly that the defendant is innocent of the crime of which he had been convicted;

- where the fresh evidence so undermines the evidence against the defendant that no conviction could possibly be based upon it;

- where the conviction rendered the conviction unsafe because, had it been available at the time of trial, a reasonable jury might or might not have convicted;

- where something had gone seriously wrong in the investigation of the offence or the conduct of the trial, resulting in the conviction of somebody who should not have been convicted.

The Court held that categories (i) and (ii) fell within the meaning of the phrase “miscarriage of justice”, and that section 133 was compatible with article 6(2), which provides that everyone charged with a criminal offence shall be presumed innocent until proved guilty according to law.

The appeal thus obliges the Supreme Court to consider whether it should depart from its previous decision in Adams in the light of the decision in Allen v United Kingdom, where the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) held that an applicant’s article 6(2) right was not violated in a category (iii) case, and in the light of the introduction of section 133(1ZA), which defined “miscarriage of justice” so as to limit the entitlement to compensation to category (i) cases.

Lord Mance holds that whether there exists a link between the criminal charge and, for instance, civil proceedings arising from the same facts is a diversion from the real question, namely whether the court in addressing the other, civil claim has suggested that the criminal proceedings should have been determined differently. If it has, it has exceeded its role. Lord Mance would refuse to depart from Adams or follow the case law of the ECtHR if and insofar as the ECtHR may have, in the past, gone further than this.

Even if that is wrong and article 6(2) is in fact engaged, a separate question arises of whether section 133(1ZA) is nevertheless compatible with the Convention because it confines compensation to cases where the newly-discovered evidence shows beyond doubt that the defendant did not commit the offence. This question has never been directly before the ECtHR or decided by it, and Lord Mance is far from confident that the Court would conclude that section 133(1ZA) is incompatible if the question were argued before it.

Although it is in general wise for the Supreme Court to find that an applicant’s rights have been breached where it is clear that the ECtHR would find a violation of the Convention, Lady Hale is persuaded that it is not so clear in this case. Her Ladyship agrees with Lord Reed that article 6(2) is engaged, but it does not follow that the ECtHR would automatically find a violation. She also agrees with Lord Mance’s formulation of the test. Lady Hale also considers the ECtHR’s jurisprudence in this area to be evolving and it is not appropriate for the court to make a declaration of incompatibility in proceedings brought by an individual in respect of whom the ECtHR would be unlikely to find a violation (the facts of these cases being equivalent to those in Allen where no violation was found).

Lord Wilson would dismiss the appeal on the basis that the ECtHR’s case-law on article 6(2) has become hopelessly confused. Lord Wilson cannot subscribe to the ECtHR’s analysis in this area, despite the high professional regard in which he holds its judges, the desirability of a uniform interpretation of article 6(2) throughout the states of the Council of Europe, his belief that there is no room left for further constructive dialogue between this court and the ECtHR, and his recognition that the appellants are likely to prevail before the ECtHR in establishing a violation of their Convention rights.

Lord Hughes would dismiss the appeals for reasons which substantially, although not explicitly, overlap with those of both Lord Mance and Lord Wilson. Different legal systems adopt different compensation schemes for those wrongfully convicted and, in some jurisdictions, even for those who were detained pending their trial. The ECtHR has been at pains to say that neither article 6(2) nor any other rule provides an unqualified right to be compensated in such circumstances. A person who seeks compensation after their conviction has been quashed is merely seeking to bring himself within the legitimate restrictive eligibility requirements for such compensation. Thus, even if there existed a workable test for finding the requisite “link” between an earlier (eventually quashed) conviction and the later compensation proceedings, such a link would not exist in this case, because the latter can only be said to be based on the former to the extent that the first condition for eligibility for compensation is that a conviction has been quashed.

Lord Lloyd-Jones agrees with Lord Mance and attaches particular importance to the fact that the ECtHR has not yet directly addressed the issue of why it is objectionable to require evidence establishing innocence but it is not objectionable to require evidence establishing that the claimant could not reasonably have been convicted. Having regard to the unsettled state of the ECtHR’s case law, Lord Lloyd-Jones is not persuaded that section 133 is incompatible with the Convention. These matters require consideration by the ECtHR.

Lord Reed would have allowed the appeal. The critical factors (identified by the ECtHR in Allen) in establishing the necessary link are that the quashing of the conviction is a prerequisite of proceedings under section 133 and that in order to arrive at a decision on the claim it is necessary for the Secretary of State to examine the judgment of the Court of Appeal to determine whether the criteria of section 133 were satisfied. Whilst it may be appropriate for this Court to decline to follow the ECtHR in certain circumstances, no circumstances of that kind exist here: the Grand Chamber’s judgment in Allen was carefully considered, is based on a detailed analysis of the relevant case law, is consistent with a line of authority going back decades, and has been followed by the ECtHR subsequently. In the absence of some compelling justification, Lord Reed finds it difficult to accept that this court should deliberately adopt a construction of the Convention which it knows to be out of step with the ECtHR’s approach, established by numerous judgments, and confirmed at the level of the Grand Chamber. Lord Reed accepts that the implication of the decision in Allen is that it is not necessarily incompatible with article 6(2) to refuse compensation under section 133 in in category (iii) cases, but holds that section 133(1ZA) is not compatible with article 6(2), because it effectively requires the Secretary of State to decide whether persons whose convictions are quashed have established that they are innocent.

Lord Kerr agrees with Lord Reed. For the reasons given by Lord Reed, Lord Kerr considers that there exists the requisite link between the concluded criminal proceedings and the compensation proceedings, which is the test articulated in a clear and constant line of Strasbourg jurisprudence. His Lordship also rejects Lord Mance’s formulation of the relevant test because it would cut out a swathe of deserving applicants who are unable to prove their innocence even though they are, in fact, innocent and the fate of applicants would be determined by the phraseology that happened to be chosen by the court.