Irish Legal Heritage: Mamie Cadden

On 1 February, the Feast of Saint Brigid of Kildare is celebrated as the day of new beginnings, the beginning of spring, and stories are told of the many miracles attributed to the second patron saint of Ireland.

Probably the most famous of her miracles is the story of her asking God to soften the heart of the King of Leinster so she could use his land to build a convent – the story goes that the King agreed with Brigid that he would give her as much land as her cloak would cover, not expecting her cloak to grow and cover land as far as her maidens could walk with its four corners. The lesson for the King was that, by giving Brigid’s cloak the power to cover all of Leinster, God was punishing the King for being mean to the poor. The frightened King ended up giving Brigid the land she needed, helped her to build the convent, and became a good Christian himself.

A perhaps lesser-known story of the saint, said to have lived in fifth and sixth century Ireland, was the miracle of the “Pregnant Women Blessed and Spared the Birth-Pangs”. In S Connolly and JM Picard’s translation of Cogitosus: Life of Saint Brigit, the story reads:

“With a strength of faith most powerful and ineffable, she blessed a woman who, after a vow of virginity, had lapsed through weakness into youthful concupiscence, as a result of which her womb had begun to swell with pregnancy. In consequence, what had been conceived in the womb disappeared and she restored her to health and to penitence without childbirth or pain. And, in accordance with the saying ‘All things are possible to those who believe’, she went on working countless miracles every day without anything ever proving impossible.”

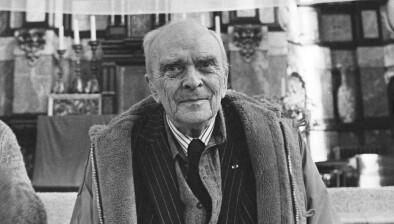

In stark contrast to Brigid’s sainthood, women in Ireland who caused “what had been conceived in the womb” to disappear were far from celebrated. One of these women, Mary Anne “Mamie” Cadden, is just one of the many women prosecuted for “procuring a miscarriage”.

In 1926, Mamie qualified from the National Maternity Hospital in Dublin as a midwife. In 1929, she set up her first maternity nursing home in Ranelagh, moving to Rathmines in 1931. Throughout the 1920s and ’30s, Mamie developed a reputation as a midwife who offered “extra services” to expectant mothers – which included procuring abortions and placing unwanted children for adoption (See Ray Kavanagh, Mamie Cadden: Backstreet Abortionist).

Mamie’s first major run-in with the law came in 1938, when she was charged with “child abandonment”, and sentenced in 1939 to a year’s hard labour in Mountjoy. When she was released from prison, Mamie was removed from the roll of registered midwives, but she continued working illegally as a well-known abortion provider in Dublin.

In 1945, Mamie was tried under the Offences Against the Person Act 1861, convicted of “procuring a miscarriage” for a woman, and sentenced to five years penal servitude in Mountjoy. Undeterred, when Mamie was released, she offered her services again – so famous that she did not need to advertise.

In 1956, Mrs Helen O’Reilly – a 34-year-old mother of six – died as a result of a backstreet abortion in Mamie’s illegal nursing home on Hume Street (See Cara Delay, Kitchens and Kettles: Domestic Spaces, Ordinary Things, and Female Networks in Irish Abortion History, 1922–1949). Mamie was convicted of Helen’s murder and sentenced to death. After public appeals for clemency and recognition of the lack of mens rea, Mamie’s capital conviction was commuted to life imprisonment. In 1958, Mamie was transferred to the Central Criminal Lunatic Asylum where she died in 1959.

Mamie was one of many women who were subjected to abortion prosecutions in Ireland, whether as a result of accidental death from the procedure or because someone gave them up to the authorities. Delay’s research describes the network created by Irish women to assist each other in making reproductive choices – and highlights the normality of women, in all walks of life, who sought, for whatever reason, for “what had been conceived in the womb” to disappear.

Seosamh Gráinséir